14 August 2017

Git Branching Strategy for Feature Development

Git is a powerful tool that let’s you manage your source code pretty much any way you want. But this is definitely a case of “all things are permissible, but not all things are beneficial.” What I’d like to do is lay out my strategy for managing feature branches.

I’m going to jump to the punch line. Here’s my overall recipe for merging a feature branch assuming all work on the branch is done:

git checkout mastergit pull --rebasegit rebase --committer-date-is-author-date master feature-branchgit checkout mastergit merge --no-ff feature-branchgit push origin master

Why do we use feature branches? There are three goals to keep in mind. First, it’s very nice to see all the commits grouped together that make up a chunk of development. Second, we still want to make it easy to browse the git history and make sense of what’s going on. Third, the master branch is considered golden. At any time, master should be able to be deployed at least to a staging environment if not directly to production. There are other benefits for sure; but these are my three primary goals when figuring out my workflow.

Rather than just dictate to you that my recipe is the best way, I’m going to walk through a couple options of how you could handle branching and merging. Along the way, we’ll see how well these options hold to the three goals outlined above. I consider most of the examples wrong. In various ways they don’t meet the goals of clarity, grouping chunks of work, and leaving master production ready.

Also, before we dive in too deep, I’d like to put in a plug for Git Immersion. It’s a course put together to help people understand what git is doing. Jim Weirich wrote the course. He was a master teacher. While he was certainly super nerdy, he made technology very approachable. Don’t be afraid of the innards of git. If you’re not super comfortable with it, you should work through the course with Jim.

Pulling from Master

Here’s the first step. Consider the following situation:

You’ve made a change directly on master and there are changes made directly on master from your remote. If you simply git pull, your changes will be merged into the remote’s master with a merge bubble:

git pull

This is confusing to read. There’s an “extra” commit representing the merge itself. The two commits appear to be on different branches even though both were made directly onto master. At first glance, I’m not sure what’s just happened here. Was the branch made on purpose? Did it represent some feature work? I can reason it out in a couple seconds, but it’s ugly and confusing at first glance. This confusion is just a wart due to committing code from different locations.

The solution to this is always pull from your git remotes with --rebase. This will cause your local commits to be rewritten directly on top of the remote’s master.

git pull --rebase

This is clean and clear. There were two commits in a row directly on master. That the commits were made on different systems is irrelevant.

Creating a Branch for your Feature

When you begin development on a new feature you think might take a while, start by creating a new branch. There are several ways to create a new branch. My favorite is like this:

git checkout -b feature/fancy-feature

This actually is switching to a branch by checking it out. The -b flag tells git to create the branch since it doesn’t yet exist.

In this case the name of the feature is fancy-feature. Using the feature/ prefix on your branch name gives it a sense of organization. I’ll also sometimes use bugfix/.

On this branch you can develop to your heart’s content. Though I will point out that “long lived” branches can create problems. It increases the likelihood that your changes on the branch will conflict with those on the mainline master branch. It also makes it more difficult to actually integrate the new functionality back into mainline master.

I’m going to largely gloss over the work done on the branch. If the work is done in a relatively short period of time, it’s pretty much no big deal. You simply do periodic commits of work on the branch. When you’re done with the feature, you begin merging it as below. However, for longer lived branches you may have to do more work to keep your branch in sync with the work that’s continuing on the master branch. There are some other odd ball scenarios that can cause confusion as well. For the time being I’d like to forget about all that and focus on how to merge your branch back into master after you’ve finished working on the feature.

Branch Merging Scenarios

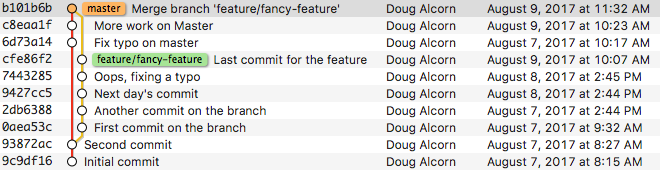

After you’ve done development on your branch, imagine you have a scenario like this:

Here’s a situation when you have several commits on your branch, but other commits are on master. The goal is to merge the branch into master, but there are a few options.

Option 1

First, you could simply merge as is. What you’d end up with is something like this:

This isn’t all bad. It meets our first goal above of seeing all the commits for the feature in one chunk. There are some confusing parts though. At first glance it looks like the “Fix typo on master” commit happened after all the development on the branch (which it didn’t based on the commit date).

Option 2 (Step 1)

One thing you could do to fix this is rebase your branch off of master before you merge. I do this with the command:

git rebase master feature/fancy-feature

The result looks like this:

This is the default for rebasing a feature branches. But there’s a couple things to note here. First, the act of rebasing the branch creates new commits. They have a different sha. Before the rebase “First commit on the branch” had a sha of 0aea53c. After it’s 4029f03. Second, this new commit also gets the timestamp of when the rebase was done. We’ve lost information of when the commit was made. Looking strictly at this log, it seems like no work at all was done on 8/8.

###Option 2 (Step 1 Even Better)

Here’s something new I learned recently to fix the problem of changing the commit date:

git rebase --committer-date-is-author-date master feature/fancy-feature

As it turns out, git remembers when the commit was originally authored when it’s rebasing. The option above will use the author date as the commit date rather than the current date: The result of this command looks like this:

Now all the timestamps on the rebased branch have the original commit date. All of the commits that were on master before the rebase are below the branch’s commits. The branch itself is a single line of commits on top of master.

Option 2 (Step 2)

Finally, here’s the last step in my preferred merge strategy:

git checkout master

git merge --no-ff feature/fancy-feature

And the resulting merge bubble:

This meets all the goals of doing a good merge. All of the commits from the branch are together. The graphical log is simple in that the only branching is for the commits specifically on the feature branch. Further, timestamps are preserved.

There’s another effect here with respect to integration. The general concept is that the commits on master are already integrated. The code on master should be ready to go to production at any time. By rebasing the feature branch on top of master, it’s up to the feature branch developer to resolve all conflicts and integrations before merging back into master.

Option 2 (Step 2 But Worse)

If you do the above merge without the --no-ff option,

git checkout master

git merge feature/fancy-feature

What happens is that the commits are re-written onto master, but there’s no merge bubble. In git language, you are “fast forwarding” master with the branch:

We’ve missed our primary goal. The group of commits that make up the feature have been lost. They look just like a series of commits made directly on master. There’s no way to tell that there was several steps required to implement the feature.

##Conclusion

These examples have been fairly simple. Here’s a real world example of what happens when you don’t rebase feature branches before merging them. This graph corresponds to about three days of work. Even under the best of circumstances, it’s easy for things to get out of control. Looking at this graph, it’s very difficult to see what code is where:

Follow this recipe:

git checkout mastergit pull --rebasegit rebase --committer-date-is-author-date master feature-branchgit checkout mastergit merge --no-ff feature-branchgit push orign master

Make sure your merge looks like this:

Only the commits from the branch are inside the bubble. All of the changes on master should be below your merged branch. Your merge commit should be the last commit on master.

If you don’t have a merge that looks like this – do not push master back to origin. You can start over and try again:

git checkout master

git reset --hard origin/master

This will make your master exactly like the remote’s master. At this point you can try again to follow the recipe above to get a clean merge bubble back onto master. As long as you don’t push back to origin, you can pretty much recover from any mistake you might make locally.

Good luck!